Sklansky Malmuth

Authors Ed Miller, David Sklansky, and Mason Malmuth

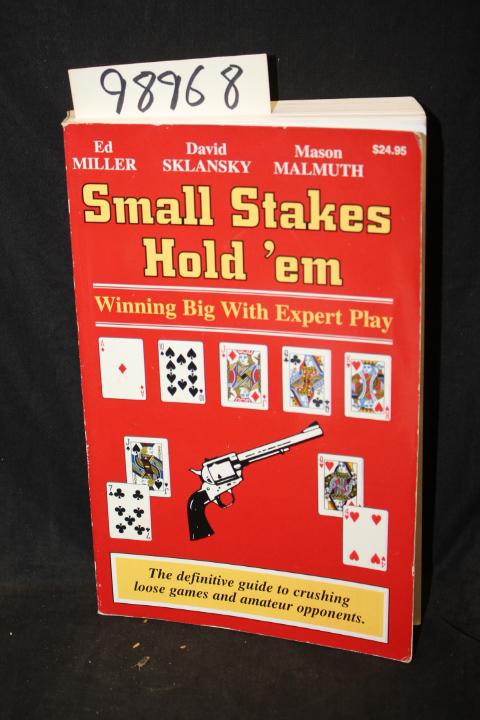

Small Stakes Hold’em, by Ed Miller, David Sklansky and Mason Malmuth November 6, 2007 at 9:51 PM August 11, 2020 at 7:58 AM by Staff Small Stakes Hold’em brings together three of the games most notable theorists to teach you how to crush low limit hold’em games. The Sklansky and Malmuth starting hands table groups together certain hands in Texas Hold'em based on their strength. Starting with the strongest set of hands that you can be dealt in group 1, the hands get progressively weaker working down the table until the virtually unplayable hands in group 9.

Find out how to qualify for this book in the Two Plus Two poker bonus program

Synopsis of Small Stakes Hold'em: Winning Big with Expert Play

For today's poker players, Texas hold 'em is the game. Every day, tens of thousands of small stakes hold 'em games are played all over the world in homes, card rooms, and on the Internet. These games can be very profitable -- if you play well. But most people don't play well and end up leaving their money on the table.

Small Stakes Hold 'em: Winning Big with Expert Play explains everything you need to be a big winner. Unlike many other books about small stakes games, it teaches the aggressive and attacking style used by all professional players. However, it does not simply tell you to play aggressively; it shows you exactly how to make expert decisions through numerous clear and detailed examples.

Small Stakes Hold 'em teaches you to think like a professional player. Topics include implied odds, pot equity, speculative hands, position, the importance of being suited, hand categories, counting outs, evaluating the flop, large pots versus small pots, protecting your hand, betting for value on the river, and playing overcards. In addition, after you learn the winning concepts, test your skills with over fifty hand quizzes that present you with common and critical hold 'em decisions. Choose your action, then compare it to the authors' play and reasoning.

This text presents cutting-edge ideas in straightforward language. It is the most thorough and accurate discussion of small stakes hold 'em available. Your opponents will read this book; make sure you do, too!

Excerpt from the Book Winning Big with Expert Play: Pairs Smaller than Top Pair

When you have a pair smaller than top pair, the probability that you have the best hand is obviously reduced. You usually play these hands under one of two circumstances:

- No one has shown much strength, so you might have the best hand.

- The pot is large, and you are drawing to a probable winner.

on a flop of

This is a very strong hand. You have middle pair, ace kicker, and the nut-flush draw. If no one has a queen, you will usually have the best hand. Even if you are behind to someone with a queen (but not ace-queen), you have fourteen outs (3 aces, 2 sevens, and 9 hearts) to overtake him. Even against a large field, you will often win. You should usually raise and reraise with this hand on the flop, especially against multiple opponents. With so many outs you will usually have a lot of pot equity, even if you do not currently have the best hand.

on a flop of

This is a strong hand. You have bottom pair with a small flush draw. Although obviously not as strong as the previous example, this is still a robust holding. Your bottom pair, no kicker is not likely to be the best hand unless you are heads-up, but you still have a fourteen out draw. Any time you flop a pair and a flush draw, you have a strong hand.

on a flop of

This is a strong hand (though it is on the low end of that category). You have a pocket pair much higher than middle pair. If you have the best hand, you are unlikely to be outdrawn. Only one additional overcard can come, and there are no straight or flush draws. If someone has a king, however, you are drawing to two outs.

on a flop of

This is a marginal hand. You have middle pair, ace kicker. You may have the best hand. If you do not, you have five outs to two pair or trips and a backdoor flush draw. Between this hand and the previous one, if no one has a king, the queens hand is stronger; fewer overcards can outdraw you. But if someone does have a king, this hand is stronger, since you have more outs.

on a flop of

This is a marginal hand. You have a pocket pair higher than middle pair. This hand combines the weakness to overcards of the ace-seven hand with the lack of outs of the queens hand. Despite being a higher-ranking poker hand than ace-seven (a pair of eights versus a pair of sevens), this hand is clearly inferior to both the queens and the ace-seven hands. (For a similar example, see p. 88 of The Theory of Poker by David Sklansky.)

on a flop of

This is a poor to marginal hand. You have a pocket pair higher than middle pair. You may have the best hand. If you do, the three big cards and two-flush are dangerous. They make it likely for someone to have flopped a pair or a straight or flush draw (though you do hold two 'stopper' cards for many of the possible straights). If behind, you are drawing to two outs and a backdoor straight draw.

on a flop of

This is a poor hand. You have bottom pair and the bottom end of a one-card gutshot. You are unlikely to have the best hand. If you catch a nine, anyone with a bigger two pair or a queen beats you. If you catch a queen, anyone with an ace makes a bigger straight. This hand will make a second-best hand far more often than it makes the best hand, and in most circumstances you should fold it.

on a flop of

This is a poor hand. You have a pocket pair higher than bottom pair. You are unlikely to have the best hand. If you do, someone could catch a flush, straight, or one of seven overcards to beat you. If you are behind, you have two outs to improve. One of those outs, the 6d, puts three to a flush on board. In a multiway pot your hand is terrible (although you should take a card off getting 30-to-1 odds or so which sometimes happens).

Sklansky Malmuth

Other Books Written by Ed Miller and David Sklansky

Other Books Written by Ed Miller

Other Books Written by David Sklansky

Somewhere along the way David Sklansky and Mason Malmuth began inserting “A Note on the English” among the prefatory materials of their books. I know it appears at the beginning of Hold ’em Poker for Advanced Players

and Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players -- it might turn up in other books as well. The note concerns the issue of style. After talking a little bit about how they compose their books (via tape recorded conversations later transcribed), Sklansky and Malmuth admit that what results may not read as smoothly as one would hope.

and Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players -- it might turn up in other books as well. The note concerns the issue of style. After talking a little bit about how they compose their books (via tape recorded conversations later transcribed), Sklansky and Malmuth admit that what results may not read as smoothly as one would hope.“But the purpose of this book is not to get an ‘A’ from our English teacher,” the note goes on to say (in Hold ’em Poker for Advanced Players). “Rather it is to show you how to make a lot of money in all but the toughest hold ’em games. So if we end a sentence with a preposition or use a few too many words or even introduce a new subject in a slightly inappropriate place, you can take solace from the fact that you can buy lots more books by Hemingway with the money we make you.”

I’ve never been a big fan of utterly dismissing the importance of style like this. Anyone who tries to communicate via the written word knows that how one says something oftentimes can be as important as what one says. Obviously Sklansky and Malmuth had been faulted by someone somewhere for their style and so decided to try to head off that particular criticism before it arose.

Frankly -- as someone who has read several books by either Sklansky, Malmuth, or both -- I’ve never been that bothered by their style. All of their books (to me) seem well organized and well written (if a little unexciting at times). In other words, not only do I tend to disagree with the disclaimer’s suggestion that style is unimportant, I wouldn’t think these two should feel obligated to say such a thing about their books.

In any event, I was reminded of the pair’s attempt to dismiss the importance of style earlier in the week when I read a post over at Kick Ass Poker reporting a recent flare-up over on 2+2 that involved something Malmuth and Sklansky wrote. Most specifically, how they wrote it.

Allegation and Response

For those who missed it, earlier this month a poster on 2+2 began a thread titled “plagiarism? looks like it to me” in which he quoted a passage from Malmuth and Sklansky’s Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players (first published in 1989, I believe) that closely resembles a passage in Chip Reese’s stud section of the original Super/System (first published in 1978). Don’t bother looking for the original thread anymore. It’s vanished.

Sklansky And Malmuth Starting Hands

Both of the passages in question concern the concept of raising with a so-so hand on fourth street when heads-up to try and get a free card on fifth while also anticipating the possiblity that you might get a big card on fifth and thus have to bet first (potentially nullifying the ploy to get checked to on fifth). The idea here is that you don’t want to have to bet first on fifth in this situation unless the card you catch is giving you some more hand-building possibilities (like making a big straight).In Super/System, Reese writes “Suppose you have up and the in the hole. Your opponent started with a King-up and caught a Baby on Fourth St. Now, if you catch a King or an Ace, you’ll be high but it won’t wreck your play because you’ll have a chance to make a straight.”

In Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players, Sklansky and Malmuth write “Another example. You have () and your opponent started with a king up and caught a baby on fourth street. Raise if he bets. Notice that if you catch an ace or a king, you have improved your hand since you now have straight potential.”

(Incidentally, what I’m showing you here is how the original poster quoted the two passages. I’m noticing in Super/System a couple of small, superficial differences in the quote. I don’t have a copy of Seven Card Stud here to compare.)

You get the idea. Same concept, expressed in nearly the same terms, and even using the same example. Coincidence? Probably not.

As Haley explains over on Kick Ass Poker, the initial response to the accusation from Malmuth was a flat denial. Additionally, the poster (and some others, apparently) were banned. As I mentioned, the original thread was removed, although a few others have popped up in which one can find the original post being quoted and discussed. Among those, you might start with this thread that discusses the original thread (in “Books and Publications”) being locked (and later removed).

Eventually Sklansky ended up addressing the matter, and in a Dec. 10th post admits that in fact the passage in question very likely resulted from the pair’s technique of recording conversations and then transcribing them. As Sklansky explains, he was giving Malmuth lessons about stud and the pair was tape recording them, not necessarily even thinking about writing a book until later. Sklansky admits one thing “I do remember well was that I had uncharacteristically learned something from someone else’s book,” namely Super/System, and that as “I was giving Mason lessons I made sure to include that concept.”

Somewhere along the way, Sklansky explains, giving credit to Reese for the idea/example was lost in the shuffle. “Perhaps I got the book and read Mason the example,” says Sklansky. “In any case by the time Mason got around to transcribing his tape he forgot or didn’t realize that this one example came straight from Doyle’s book. And when I checked the manuscript, I wouldn’t have remembered, since I only remember general concepts not details.”

All in all, a fairly innocent mistake, I’d say. Even so, the initial strategy of denial, removing and/or locking threads, and banning posters seems (on the surface) doesn’t seem all that reasonable of a response to the accusation. (There’s more to that part of the story. If you’re really curious, you might look back at this thread which includes a quote from Malmuth explaining why some of the posters were banned from the site.)

What is animating some 2+2ers is the fact that both Malmuth and Sklansky have always been exceedingly conspicuous about giving credit where credit is due whenever the two of them are concerned. (Note Sklansky saying he “uncharacteristically” learned something from someone else.) A brief search around 2+2 shows dozens of examples of one or the other claiming credit for ideas/concepts appearing in others’ books. In other words, some here are obviously energized by the irony of a situation in which the pair who so often claim themselves “original” having not only gotten an idea from someone else but failed to give proper credit.

Sklansky Malmuth Hand Groups

Obviously in future editions the pair should add a citation acknowledging Reese as having come up with the idea/example. And like I say, I don’t think the offense here is nearly as egregious as, say, the one perpetrated by that website I found while writing this post that essentially transcribes all of Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players. I did want to add one last observation, though. One that goes back to that “Note on the English” with which I began.

The Significance of Style

Part of the defense against charges of plagiarism rests on the notion that style shouldn’t matter -- that how someone writes is not as a important as what someone is trying to say. Of course, the uncredited borrowing from Reese involves both form and content -- both the idea and the way it was presented. It appears that both the accusers and the accused are much more concerned here with form than with content -- with the lifting of exact words and phrases, not the claiming of another’s idea as one’s own. Not necessarily surprising as far as the accusers are concerned (the exact replication of words/phrases is what originally got their attention), but actually quite surprising with regard to the accused.

Look at how Sklansky concludes his defense (from the post alluded to above):

“But duh. Cmon. How easy would it have been for me to come up with a completely different example to perfectly describe the exact same concept? To ascribe this to anything other than an oversight is completely ridiculous. Chip’s chapter was very good but it was 50 pages. Our book has 300.”

As in the “Note on the English,” we are being encouraged not to be overly concerned with how something has been written. What we have here is a completely functional view of style, one implying that words and phrases can be infinitely altered and interchanged without affecting the underlying meaning (the “concept” being advanced). I could have come up with a different example, says Sklansky, and it wouldn’t have affected the communication of the idea. While we know (or should know) that form does affect content, we see what he’s saying. Sure, change around the exact cards and the wording -- we’ll still get what you’re trying to tell us about getting that free card on fifth.

But wait a minute. Is Sklansky suggesting it would have been just fine to borrow Reese’s idea and present it in a different form -- that doing so would make the idea somehow “original” to the authors of Seven Card Stud for Advanced Hold ’em Players? I cannot believe Sklansky really means to imply that, but that’s precisely what he has done.

I think a lot of the difficulty goes back to that functional view of style, which might also be regarded as an attempt to quantify what can’t really be quantified. (Sklansky’s reference to the number of pages in Reese’s chapter versus the pair’s book might be regarded as another example of this tendency.) I would argue that dismissing style as unimportant -- or purely functional -- creates conditions in which uncredited borrowing is more likely to occur. Indeed, the fact that carelessness about style often leads to carelessness about content might be said to prove a relationship between the two.

Writers simply have to care about style, or risk not knowing what exactly they are saying (or how they are being understood). Precisely where I think Sklansky finds himself at the end of that post -- namely, having adopted a paradoxical stance on the matter that fails to demonstrate the logical rigor for which he is often (rightly) celebrated.

Do you see why?1

[1] David Sklansky, passim.

Labels: *the rumble